TRIP LOG

March 6, 2019

-Planning-

The US airspace system was largely developed in the decades following the second world war. As military aviators returned to regular life and technologies honed during the war were translated in to new, affordable private aircraft designs, a whole generation Americans took to the air. Thousands of new airfields popped up in big cities and small towns across the country. The promise of new economic benefits from business air travel and air taxi service prompted remote communities from coast to coast to build landing strips, hangars, and terminals that increased their accessibility. This period of rapid expansion is now long-passed, but more than 5,000 public-use airports remain across the US. Many of these continue to provide convenient access to towns that are otherwise off the beaten path.

Aviation has been a passion of mine since childhood, and in the past 5 years I have begun to work flying into my personal and professional life. I am a 50% owner of a 1961 Cessna 182 (Skylane), N8876X, like many private aircraft remaining in the US general aviation fleet also a product of the post-war flying boom. I have enjoyed traveling across the western states for sight-seeing, vacation, and occasionally to attend a scientific conference or visit a field research site. As the FIND-EM project developed, it became clear that the capabilities of a light airplane like 76X to traverse large parts of the country relatively quickly and land at most any airfield, large or small, could be a great resource for our field sampling.

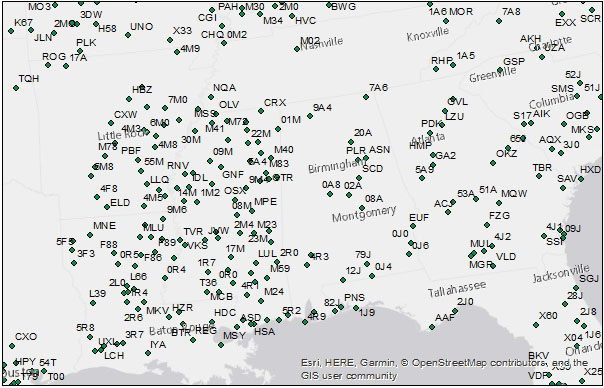

Fortunately, many airports, particularly in more remote areas, have their own water supplied from on-site wells or have been tied into town water supplies that are entirely groundwater-served. My planning began, then, with GIS data layers recording the distribution of more than 800,000 water wells across the US and all publically-accessible airports. After some analysis I identified about 750 airports in the southern half of the country that had one or more wells nearby. Next came some hypothetical trip planning. Which airports could I expect to get into/out of? How could these be linked together into a cross-country flight that consisted of a realistic and safe number of flying hours per day and allowed me to cover the target area in the time available?

Once I had a list of candidate airports in mind, the next step was to start reaching out to airport managers across the country to find out what they could tell me about the water supplies on their fields. I have a list of more than 100 airports in hand, and am still working my way through it. So far I’ve found that everyone I’ve talked to has been friendly and willing to take a few minutes to answer my questions. This is pretty typical for the aviation community...in almost all of my interactions I’ve found folks to be friendly and eager to share their knowledge and help out. I’m guessing that for most of the folks I’ve contacted this is the only time this year they’ll be asked about the source of the water at their airport!

All this has led me to a set of provisional plans and back-up contingencies, but the actual path and progress of my trip will be governed by the whims of the weather. Light aircraft like 76X are not equipped to deal with certain kinds of weather, and in particular winter storms with their threat of airframe icing, strong winds and associated turbulence, and thunderstorms are to be avoided. As a result, I’m now starting to add daily checks of the weather forecasts to my planning process. Today’s projections show a high pressure system over Idaho on Saturday and moving eastward to the Atlantic Coast through Tuesday. This all looks pretty good for a weekend departure from Salt Lake City and the potential to track this weather system, and the stable clear conditions it will bring, on a 4-day transit across the country. Let’s see how this forecast holds up over the coming days!

March 8, 2019

-24 hours out?-

The last couple of days have involved slow and steady preparations mixed with the day to day requirements of work and life. We’re currently interviewing candidates for a faculty position, which involves numerous talks and meetings, and a prospective graduate student is visiting to interview with our group today. I managed to squeeze in time for changing 76X’s oil on Wednesday afternoon. This isn’t glamorous work, but it’s got to be done, and it’s one of a limited number of maintenance tasks the FAA will allow pilots to do themselves. Airplane owners have varying opinions when it comes to choosing to do their own oil changes (vs. taking the plane to the shop). I’m a bit of a tinkerer, and like to do it myself if I can find the time. I also like the opportunity to look under the hood every 40-50 hours of flying and make sure I know the condition of my engine and airplane.

Yesterday I had several fascinating discussions with folks on the ground. A mayor in Missouri offered to give me a ride to several irrigation and drinking water wells in his town. On the other end of the spectrum, an airport manager in Colorado said what I was proposing made no sense to him and he wanted nothing to do with it! Overall I continue to be impressed with how open and helpful most people I talk with are. I’m also getting familiar with the consumer confidence reports our water utilities are required to issue each year. These generally contain pretty specific information on water sources, and are a great resource. Unfortunately, each state has its own system for how these are issued and accessed, some easier to navigate than others.

Along with continuing to make calls to airports I’ve been keeping a close eye on the weather. My dream that there would be a massive, stable high pressure system from coast to coast for the next 10 days is long gone, but the forecast still suggests a decent window of weather will move across the country at about the speed I expect to travel (Saturday morning forecast, below) and I’m hoping to ride this wave.

The devil will be in the details, however, especially for the first day of flying. We currently have overcast skies below the mountain tops in Salt Lake City, and are expecting snow later in the day. There should be bit of a break and lifting clouds at some point tomorrow into Sunday, but the exact timing remains uncertain. Assuming conditions shape up by around noon I’m still hoping to take advantage of this window and start east on Saturday. My goal is to head east into Northern Colorado and then toward southwestern Kansas, sampling water from a number of towns that rely on the massive Ogallala Aquifer along the way (black arrow). On that end, strong winds are predicted for much of the day Saturday, but should abate by evening.

Even ~24 hours out (and honestly right up to the moment) I can’t commit myself too strongly to one course of action. I’m keeping multiple backup options in mind, including adjusting my first-day route to the south to take advantage of warmer temperatures and higher clouds or delaying for a day if projections for Sunday’s weather become more favorable. Stay tuned to see what happens!

March 9, 2019

-We're off!-

It’s the most important decision a pilot makes...we call it “go/no go”. The captain of your Airbus still has some say in it, but the airlines have developed strict criteria that largely make the decision for them. For those of us who fly more modest machines, the guidelines are more flexible. Yet the standards we choose to impose on ourselves are designed to achieve a common goal: don’t end up in the air, wishing you were on the ground.

I set the scene in yesterday’s post, and conditions largely shaped up as predicted. Salt Lake, however, was experiencing a lingering, patchy cloud layer throughout the morning, reducing visibility just enough to encourage me to delay. By noon the clouds had lifted and thinned, and glimpses through scattered breaks made it clear that there were pathways to the blue sky above. We’re off!

The mountain interior is a land of impounded rivers, and although many communities still make use of groundwater the widespread presence and use of water from mountain reservoirs makes sampling for this trip, which targets towns supplied exclusively by groundwater, tricky. As a result, the focus of the first leg of my journey is largely to find my way over the ranges and valleys of Utah and Colorado to the Great Plains beyond. There lies one of the largest, most exploited underground aquifers in the States, the Ogallala.

In order to get there today I find I will need to push 76X higher, literally, than I’ve taken her previously. The lingering clouds over Salt Lake Valley have been pushed up against the peaks of the Wasatch, and beyond them the Uintas, the Colorado Front Range, and other high towers of rock along my path. Although the amount of moisture and energy in the air today aren’t enough to trigger towering cumulus, and the dangerous up- and down-drafts that go with them, a billowy sheet of cotton fluff drapes the ranges and makes a broken lid over the valleys. In this lies the potential for ice, which I’d like to avoid if at all possible.

Leaving Salt Lake, I am able to climb through some wispy layers without trouble. The shimmer of crystalline ice particles surrounds me as I punch through the clouds. Some of these find their way through the porous shell of my 50+ year old airplane, appearing in the cockpit as a sparse but festive flurry of glitter. Paradoxically, these ice clouds signal no danger...frozen water will not adhere to an airplane. It is areas where supercooled droplets of liquid are lofted from below that present the real hazard. Occasional billows over the mountains suggest this possibility, but I am able to make my way over them to my first destination, Vernal Utah. There, a spring tapping a shallow aquifer provides drinking water to the community. My first sample!

Over higher terrain east of Vernal, the clouds push as high as 15 or 16 thousand feet, however, and by the time I reach Colorado I am forced to climb to 17 thousand feet to stay above the layer. At this height, the air-breathing beast dutifully pulling 76X along is anemic. I would be, as well, without the bottle of compressed oxygen strapped to the seat beside me.

One of the most magical experiences in flight, is when you break through a high cloud layer into a new, hidden world above, and can see clear to the horizon across a sea of white. Although the majestic lines of the Rockies are largely obscured from view, the experience today doesn’t disappoint. And at these high altitudes, heading east, I have the benefit of a tailwind of nearly 50 knots, nudging my Cessna to over-land speeds I’ve seldom seen before.

The transition from the mountains to the plains is startling. The chaotic undulation of the ground, which as a pilot flying at relatively low altitudes requires constant focus, suddenly gives way, and in a moment you are gliding over an innocuous plain. Where you were previously scanning and hunting for a roadway or patch of valley bottom that might pass for a suitable emergency landing site, a patchwork rangeland of infinite possibility lies below. Today, this is accentuated by the clouds, which have been nearly continuous since departure, but are cut off like a pat of butter by a knife as I cross the last peaks. The second landing and second sample of the day is at Greely, Colorado. Greeley is an exception. Although they are not served by a groundwater supply, the town advertises its award-winning water, and I feel compelled to have a look at what they offer.

From Greeley east the flying is easy. I am chasing the strong north winds of the retreating low pressure system. I find remnants of these a few thousand feet above the ground, where my 50 knot tailwind has rotated and pushes me steadily to the south. The weather reports from airports ahead claim gusting 30+ knot surface winds along my flightpath, and on the ground I see direct evidence of the debris these winds have left behind. Luck is in my corner, however, and the breezes retreat steadily eastward. Even as the arc of dusk sweeps upward from the eastern horizon and I make my final landings at small farming towns in eastern Colorado and western Kansas, I have smooth, calm air to cushion my descent.

Seven landings and six samples in, we are on our way!

March 10, 2019

-Across the plains-

Today was all about the Great Plains, and they are, indeed, great. Departing Colby, Kansas to the south I traversed the Ogallala, landing at a series of airstrips deep in Kansas farm country. Like homes in a planned development, or more appropriately the Sears catalog homes of the early aviation era, the design of these airports is clearly taken from a common blueprint. The north-south runway is nearly ubiquitous, enough so that it lulls a pilot into complacency. The mental readjustment necessary when the rule is broken takes real effort. Today I find myself questioning the wisdom of the architects. A steady 10-15 knot wind from the east means that landing after landing must be accomplished using an awkward approach angle to stay aligned with the runway and a lurching, last-minute stab of the rudder to avoid scraping the tires off their hubs at touchdown.

Despite their obvious common design, each of these airports has its distinguishing characteristics, and these little anomalies make them memorable. The authorities at Hugoton, Kansas saw fit to install a crossing runway, modest though it is, that today seems visionary, as it points directly into the oncoming winds. The field at Liberal, next door, has trended the opposite direction. Great scars across the earth attest to what used to be the crossing runways of Liberal Army Airfield, now unused and unusable. Cushing Municipal has consumed an area of hayfields west of the main strip and mowed a triangle of intersecting furrows that allow landing in nearly any direction, if one trusts the quality of the surface.

From southwest Kansas I zig and zag to the east along the border with Oklahoma. In the air the radios are busy with chatter. This buzz is deceptive, though. Most small airports across the region use a single common frequency, 122.8 megahertz, for pilot communications, and radio signals broadcast from planes aloft can be detected at a range of one hundred miles or more. The situation on the ground is different. Most of the airports I’ve selected appear to be seldom used other than by the massive agricultural spray planes that sit by the side of many of the runways, awaiting summer’s return. The few people I do meet are friendly, if not always curious. Matt in Hugoton asks about my travels, and as I’m about to climb aboard 76X brings me a ball cap to serve as a souvenir of my time in western Kansas. Forty minutes later as I’m broadcasting my farewell from an airport some distance to the east he calls on the radio to wish me a safe flight.

The plains continue, and as I move east they drop out from under me. Each airport elevation is now a few hundred feet lower than the previous, and I find no need to climb to the 7,500 feet that served as my cruising altitude earlier in the day. I explore the column to find relief from today’s persistent headwinds, and by the time I reach the Cimarron River I am cruising at less than a mile above sea level. The landscape is flat but not monotonous. Pockets of badlands in dry Kansas give way to river-cut bedrock banks. And as I approach western Arkansas, nine landings and nine samples later, I get my first glimpse of hills and forests in more than a day.

The Fayetteville airport, with its single north-south runway, sits deep in valley between these hills. After the day’s travel I find the descent over terrain to be a refreshing change. This is also the first controlled airfield I’ve visited since leaving Salt Lake City, and the orderly process of negotiating my descent and landing with the tower controller is somehow comforting. I am sequenced first for landing, though the controller may regret this decision as moments later he has to ask a trailing turboprop to slow its approach speed to accommodate my landing.

As I pull up to the terminal I am greeted by a camera crew and a welcoming crowd of one hundred. I’m left wondering only for a moment, as the turboprop charter parks beside me and off-loads the University of Arkansas Razorback women’s basketball team, who have apparently made a Cinderella run at the SEC championship only to fall short in the final this afternoon. There arrival was quite a scene, and to the fans, I apologize for delaying your celebration, if only for a moment!

March 11, 2019

-Water everywhere-

A low mist has settled into the valley bottom where the Fayetteville airport lies. Although it has begun to thin and break into patches by the time I’m ready to go, I decide to make my first Instrument Flight Rules flight since leaving the Rockies.

Pilots operate under two distinct protocols when planning and executing their flights. Visual Flight Rules (VFR) is my standard for this trip – if you are operating a personal flight and can see where you are going and what you are about to run into, you can fly under VFR and take advantage of the flexibility it offers. A VFR pilot can fly almost anywhere, change course on a whim, and move freely through the atmospheric column to seek out the best winds and smoothest ride.

By filing and flying an IFR flight plan, the pilot gives up this independence and agrees to follow procedures encoded in government IFR charts and the instructions of a FAA employee. In relinquishing a level of freedom and flying “in the system”, one gains the support and council of the air traffic controller. Omniscient but not omnipotent, the controller sees the landscape of hazards on their computer display and issues alerts to pilots in the air, but has no power to intervene in the sequence of events that may take place hundreds of miles from, and thousands of feet above, their cozy cubicle.

As I climb out of Fayetteville it becomes clear that the now-sparse mist poses no threat, but the milky white patches clinging in the depressions below signal a change in the character of the land I will traverse during the day. After the frozen, crystalline landscapes of the mountains and the brown, dry expanses of the plains, I have entered a part of the country where liquid, flowing water is both master and adversary.

My path takes me northeast to southern Missouri, the sixth state on my itinerary. Along the way I will circumnavigate the high terrain of the Ozarks, which I see looming like shadows on the horizon to my east. After twenty minutes aloft I begin a slow descent into Branson, Missouri. The town is famous for its country music, but like most of my stops on this journey my cultural experience is limited to a ten-minute exchange with the employees of the M. Graham Clark Downtown airport. Situated on a beautiful bluff above a bend in the White River, Clark Downtown is characteristic of the “second airports” in cities across the country. These are often the original fields that serviced the area in days past, and are maintained to attract small planes such as mine away from busy commercial terminals developed on sprawling, sterile tracts of land at the city margins. Feeling sheepish for using the airport facilities without making a purchase, and disappointed that I won’t see more of the town, I buy a souvenir t-shirt from the airport office as a token of my visit.

Viewed from an aeronautical chart or from six thousand feet, it becomes apparent that the White River as it flows through Branson is in fact just a transient narrowing in a string of reservoirs spanning nearly half of the Arkansas/Missouri border. The dams clotting the flow of the river were installed by the Army Corps of Engineers during a flurry of activity in the mid-20th century. Among other purposes they serve to regulate the levels of downstream reaches of the river, allowing the cycle of flows and flooding to be engineered with precision. Of relevance to my travels, they also provide drinking water for a large number of communities in the surrounding region. One of the major challenges for our project will be accounting for such features of the water supply infrastructure. The mid-century completion of projects like the White River dams transformed the sources and distribution of water used in this region, and over the coming years we will work to reconstruct how these developments altered the chemistry of water consumed by residents through time.

As I leave Missouri to the south I continue to trace the path of the White River. Here I get a glimpse of the waterway in its more natural state. At bend after bend it has overtopped its banks, and the surrounding fields, roadways, and occasionally homes are inundated with its cloudy waters. As I continue eastward throughout the day this will be a familiar scene. After two days of travel over landscapes where liquid water was passed from the sloping terrain like a hot potato, I now seem to have arrived at a place resigned to accept its fate as the loser of this game. The airfield elevations attest to the land’s limited energy to participate. Differences are measured in tens of feet and the water pools readily across saturated fields and farms between the high points.

Although the landscape here is more congested with water and carved and segmented for diverse use, the pace of activity, both in the air and on the ground, is easy and reminiscent of the plains. I meet a friendly and curious semi-professional pilot in the trailer-sized airport office at Monticello, AR. He pauses from tallying his logbook hours, he says in preparation for a job interview to fly a turbine transport, to gawk at and talk about my vintage Cessna. In my experience so far, whatever their differences, pilots across the country are united in their love of two topics of conversation – the weather and airplanes. A bit further to the east I am surprised at my first glimpse of the massive, newly paved runway at the quiet, rural field nestled among the pine plantations southeast of Greenwood, MS. My confusion is resolved as I circle in to land and see a fleet of massive Boeing 777s, painted in the colors of various southeast Asian air carriers, that line an abandoned taxiway. These are in various states of disassembly, and their hulking masses in the still silence of the deserted field create an eerie atmosphere appropriate for an airplane boneyard.

The day ends in Chattanooga, TN, a destination that my new friend from Monticello helped me choose for the convenience and comfort of the overnight stay. Here I am greeted with true southern hospitality by no fewer than six ramp workers who seem to have been waiting eagerly to arrange overnight care for both me and 76X. I’ve accomplished again what I have come to realize as a realistic goal for a day’s travel, collecting from nine new communities during a manageable, if full, day of flying. Today’s effort covered the most diverse landscape, hydrologically, I’ve seen thus far. I’m eager to bring these samples back to Utah where we can start to document the chemical fingerprints they contain.

March 12, 2019

-Homecoming-

The good folks at the Chattanooga Fixed Base Operator (FBO) are as friendly and helpful this morning as they were last night. The concept of the FBO dates back to the early 20th century when the government first tried to gather the reigns of the wild and growing aviation business. As the prospect of place-to-place air transport materialized, it became clear that infrastructure and personnel would be needed to provide essential services at stopping-off points across the country. Contracts were issued to companies that would offer the fuel, mechanics, hangar space, and terminal and pilot facilities necessary to keep the lines running.

This morning the FBO staff help keep our project running by sending a shuttle to my hotel. It’s waiting ready as I check out at the pre-arranged time. 76X is fueled and parked a few steps from the terminal door. They try to talk me into the hot breakfast of eggs, bacon, and biscuits and gravy, which they have set out in the pilots’ lounge, but unfortunately I’ve already filled myself from a less-appealing buffet at the hotel. I do, however, accept their offer of a moon pie, local desert delicacy, as a parting gift. Although big-city FBOs like this one make their money servicing bigger-spending charter, private and corporate jet clients, I'm almost always impressed by how they extend their welcome to those of us who visit in more utilitarian machines.

Shortly after the climb out of Chattanooga, the Appalachians start to rise from below. Fields and monoculture tree plantations give way to diverse forests and fog-filled valleys. I’m forced to pass up one planned field covered by low stratus, but add a last minute stop at Western Carolina Regional, a lovely airport nestled deep in a fresh valley where the gentleman manning the FBO is happy to talk with me about the local water sources, the wet winter, and my travels.

Along my route, the situation and character of the airfields I’ve visited has evolved. Viewed from above, they seem reflective of the broader nature of people’s interaction with the lands they inhabit. The north-south strips of the plains fit neatly within the regular grid of farm and rangelands. They often extended well beyond their essential size, seeming to swell to fill the available space in this region of abundant land. In the southern states the fields were set in clear-cut parcels carved from the patchwork of pine plantations. From 7,500 feet, the small airports of the Appalachians are linear streaks like golfer’s divots slashed from the dense woods. Here and there, other gaps cut for pasture land and an occasional town similarly scar the hilly woodlands. A bit further along I land at a short strip that is etched awkwardly into a hillside between two open-pit mines.

My priority to this point has been a steady advance in front of an eastward-moving weather system, and to avoid disturbing my momentum lunch has consisted of simple snacks eaten aloft. Now I have nearly reached the east coast, well ahead of the storm, and begin to feel some relief from the pressure to advance. In almost every state in the nation one can find a handful of airports that, in addition to the usual support services, feature an on-field restaurant offering visitors a distinctive, even sought-after, taste of the local cuisine. These sites are more or less well known, often discussed in pilot’s lounges and online discussion groups, and a ready excuse for weekend leisure flights to chow down on a “$100 hamburger”. My destination now is not exactly a well-kept secret. The airport identifier code for Carthage Gilliam Field is BQ1, and indeed there seems to be no reason for the existence of the airport aside from Pik-n-Pig Barbeque, which serves up well-smoked brisket and savory southern sides within 100 yards of where 76X most recently touched down.

I leave Gilliam Field full and happy and quickly exit the mountains toward the southeast. In addition to my eating habits, the tenor of the flying environment is changing this afternoon. As I cross the remainder of the Carolinas the airports become more numerous and crowded. More and more tower-controlled fields are indicated by the growing density of thick blue and purple circles on my charts. With them, the air traffic, radio chatter, and number of communication frequencies requiring attention grows. I have not yet reached the coastal cities and their congested airways. Rather, much of the clutter I fly over and around this afternoon is comprised of military airfields and their adjacent protected airspace. I circumnavigate Fort Bragg and land at a public airport to its southwest, which, despite being miles from the Fort’s boundaries, is surrounded by government housing and swarmed by busy men and women in fatigues. I can’t help but think about the fact that some of the missing soldiers who are the focus of our work would have spent a small part of their lives here, training among the pines of North Carolina.

The last legs of the day take me on a zig-zag path to the South Carolina coast and over the Atlantic tidal estuaries to Georgia. This arrival is a homecoming for 76X, which was delivered new from the factory to Georgia in March, 1961. When was she first piloted over these sloughs? How long has it been since she has seen the Atlantic? The log books and registration records which document her history don’t reveal these secrets. But she is running smoothly in the thick, warm air, and I’d like to think she’s happy to be home, if only briefly.

March 14, 2019

-Sunshine State-

After four straight days aloft I took a much-needed day at sea level on Wednesday. My parents winter on St. Simons Island, Georgia, and were kind enough to host me for two nights, plus a day of kayaking in the local waterways and beach strolling. By the end of the day I could no longer feel the residual vibrations of the 230-horsepower Continental engine in my bones. This was good preparation for what turned out to be my longest flying day so far. Although my end destination, Panama City Florida, was only few hundred miles away, today’s route took me south in a sweeping U along the Florida peninsula and included more than seven hours of flying and ten new destinations.

As I wing southward along the Atlantic coast this morning the air is smooth, and after a day of rest I don’t so much mind the 15 knot headwind that adds a few minutes to each leg. The morning sun gleams off the ocean, and the seemingly infinite white sand beach stretchs uninterrupted to the horizon.

I fly at 2,500 feet through a diffuse, humid haze. Stretching from the ground to a layer of sparse clouds about 2,000 feet above me, this marks the boundary layer, the lowest reach of the atmosphere which is intimately coupled to the land below. Here, as the sun arcs higher into the midday sky, the energy of the warming surface will be concentrated in the form of uncomfortable convective currents of air. For now, I will take advantage of the opportunity to fly low to the ground, but by noon I will be expediting my climbs and descents through this layer, looking to spend as much time as possible in the smooth air above.

If there is a state in the union that is known for its general aviation culture, it is Florida. Mild weather supports a full calendar of flyable days, accommodating the schedules of both hobbyists and flight schools. Topographic barriers are non-existent, and beaches and sunny seas offer a wealth of opportunities for scenic flying. The substantial retiree community includes many fliers who adopted aviation, either as a vocation or avocation, during its 20th-century heyday, and have carried this passion with them into their later life.

All of this translates into an incredible density of airports and airplanes, unlike anything I have seen before. It seems that every community or feature along the Atlantic coast has multiple airfields, and almost all of them have a control tower to orchestrate the busy stream of arrivals and departures. I pass Daytona International Speedway, where the massive crossing runways of the airport are so close that they could be used as an extension of the race track. Just to its south, the private airfield at Spruce Creek is the center of a fly-in fly-out community known nation-wide. Similar planned developments, where you can literally taxi from the runway to your attached garage-hangar, can be found spotted across the country. Although many have struggled to achieve a marginal measure of success as the population of private pilots has slowly dwindled, here in Florida it seems to be a viable model.

Along with all of the private, charter, and commercial traffic, the skies of Florida are thick with students of the numerous university- and for-profit flight schools based in the state. These trainees place a disproportionate stress on the airports near their bases, where they circle the runways, rhythmically practicing their takeoff and landing technique. At the same time, they are gaining valuable experience communicating with air traffic control, or should be. The rapid, staccato transmissions of the tower controllers at the busiest fields, too frequently unacknowledged or misunderstood by the swarming Cessnas overhead, suggest a simmering frustration. At one of my stopping-points the pot boils over, and the controller pauses his barrage of instructions to admonish the dozen or so pilots in his airspace for their sloppiness. He recognizes that I am not one of his regular visitors and seems pleased with my crisp readback, issuing me a shortcut to land ahead of a cluster of inbound trainers. He can’t do as much for me on departure, however, and I find it hard not to be anxious about the travel time I am losing as I wait in a slow-moving queue to reach the active runway.

This round-about dip into Florida, beyond its balance of beauty and frustration, is actually a critical piece of my scientific mission. Florida is a groundwater state. Although the view from above reveals no shortage of lakes and rivers, a history of intensive land use has left many of these waterways unsuitable for human consumption. The solution has been to leverage the natural filtration and protection afforded by the geological formations underfoot. Over the expanse of geologic time, the limestone bedrock of the state has been perforated and transformed into a sponge by slightly acidic waters that continuously percolate downward along fractures and other subsurface conduits.

The surficial expression of these interactions is highlighted in the sinking sun as I traverse the landscape south of Tallahassee. These sinkhole lakes reflect the orderly collapse of the land surface as its foundation is etched away from below. The dissolution of carbonate bedrock has been essential to supporting the water demand of this populous state, but a good number of unlucky Florida home owners, who have seen their property swallowed whole, wish there was another way.

The slow dissolving of the limestone has another significance for our project, however. Florida’s carbonate bedrock, composed of the shells of countless long-dead sea creatures, is rich in strontium, one of the elements of interest in isotopic provenance work. Throughout the world, strontium is slowly leached from the geological formations around us, and the amount and isotopic composition of this element found in our drinking water and food reflects the geology of our surroundings. Strontium also has an affinity for our bones and teeth, and can easily be extracted from human remains to obtain a signature of the environment where one has lived. Here in Florida, we expect the waters to be rich in strontium and to carry a distinctive isotopic imprint of the ancient ocean in which the limestone-forming critters grew. The samples I have collected today will help us test this hypothesis, and refine our understanding of the isotopic fingerprint of service members who spent their early life in the sunshine state.

As the day comes to a close the clouds have coalesced at the top of the boundary layer, and new, higher decks have begun to push into the area ahead of an advancing cold front. I am flying IFR now, often above or between shelves of cloud that obscure my view but otherwise have no effect on the steady performance of 76X. I have placed my progress at the mercy of the air traffic control system, but this evening the system proves to be accommodating, giving me routings that take me more-or-less directly from destination to destination.

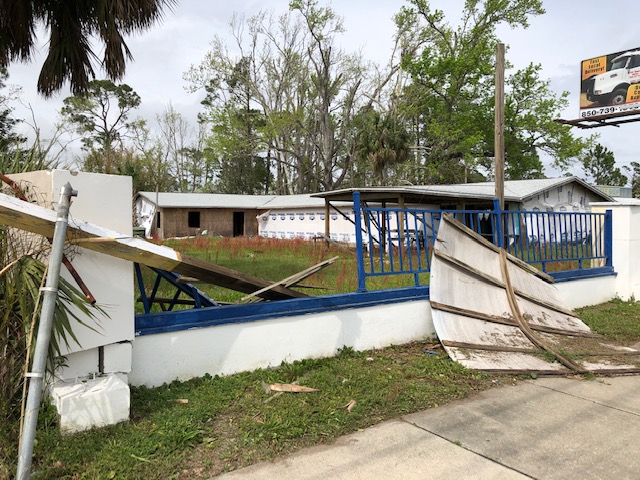

As I make my last descent of the day the sun is deeply embedded in a thick tangle of clouds to the west of the Panama City airport. I land in the twilight and taxi for what seems to be an eternity to reach the end of the 2-mile-long runway. I intend to spend the day here tomorrow, waiting for the cold front and any associated thunderstorms to pass by, before continuing west. The forests lining the highway to the city are littered with downed pines, remnants of the passage of Hurricane Michael. Although I likely could fly on tomorrow, the fallen timber reassures me that I’ve made the right decision.

March 16, 2019

-The Deep South-

A light drizzle soaked the tarmac of the Panama City airport as I loaded up 76X this morning. Pilots of piston single-engine aircraft often have strong personal opinions about the merits of Cessna's high-wing versus the below-cabin wing used by most other manufacturers, but there is no denying that on a morning like this the shelter of the wing overhead makes staging and loading the cabin a more pleasant experience.

Yesterday was spent writing, catching up on neglected email, and walking through Panama City Beach, which is still in the midst of recovery from Hurricane Michael. Most of the massive beach-front hotels seem to have either made it through the storm or finished their repairs on an accelerated schedule. The same can’t be said for the homes and businesses that lurk in their shadows. Downed trees, broken fences, and blue-tarped rooflines are common symptoms, but what I notice more than anything else are the store-front signs which are nearly ubiquitously shredded or toppled. Perhaps it is no surprise, then, that the smartest-looking store I pass is that of a sign and awning company. Just down the road their employees are busy re-installing a massive bull in front of one of the many miniature theme parks that line this stretch of highway.

Today I fly generally westward, making stops at towns, and cities, and occasionally at an airport that doesn’t appear to be associated with either. Before long I cross the Mississippi River for the second and last time on this trip. Here in southern Louisiana it is a drunken river, stumbling back and forth along massive bends as fumbles its way to the sea. The landscape west of here is saturated with waters that would like to follow along, but just can’t seem to find the energy to get up and move. From aloft, the maze of backwater channels carved through the swamps look like the streets of a European city. Despite all this surface water, most towns in this part of the country rely on wells extracting from hundreds of feet below the surface.

Lafayette, Louisiana, is a stop that brings back some memories. I spent a summer working here in the late 1990’s, my first exposure to the deep south. One of my co-workers owned a Beechcraft Bonanza that he based at this field. I remember this as one of my first experiences that showed that it was possible for a real working person to own and operate an airplane. A bit further along, I stop to collect my 50th sample at Lake Charles. Here, the FBO has a reputation for their $1 lunch offerings – substantial helpings of Cajun cuisine on offer to visitors who stop in and fill up their tanks. Saying no hardly seems like an option, and I end up with a delicious mixed plate of catfish and shrimp etouffee.

From this point the land begins a slow drying. The standing water of the swamps gives way to forest and, as I enter east Texas, reluctantly transitions to patchy rangeland. Steer line the fields beside the runway at Liberty. As I sweep north around the busy Houston airspace I begin to notice surface water reservoirs reappear. Since leaving the Carolinas the land below has lacked the relief to effectively trap and store drinking water, and what engineering projects did exist were targeted at creating dry, rather than wet, land. Now that a few hundred precious feet of elevation are available to drive the downward percolation and runoff that dry the surface, infrastructure to impede these processes seems to be required.

This evening I stop in Austin to spend the evening with my sister and meet my new niece. The primary water source to Austin residents is a surface reservoir, but I collect a sample here, anyway. I’m curious to see what it looks like, chemically. Over the coming year, the isotope chemistry of these waters will be locked into Ruby’s growing body, and become a part of her. It’s science, but when one is holding a small child and thinking about it from her perspective it’s also a little bit magical.

March 17, 2019

-Texas-

This is the first day of my travel that will be spent entirely in one state, and, appropriately, that state will be the vast and diverse land known as Texas. At the pace of my traverse and height of my vantage point, however, changes in the landscape below are frustratingly subtle and gradual. An undulation is added or a color fades. But from Austin to El Paso the palate remains drab olive and dusty dun, even as the rise and fall of the surface is progressively amplified.

The weather has turned in my favor. Sparse clouds provide occasional shade from thousands of feet above, but at the altitudes accessible to 76X as we hop across the state my visibility is unobstructed. The winds have become benign and favorable, nudging me along and adding five or ten knots to my progress each hour. The sun is powerful enough to stir up the air down low, and landings still require readiness to respond to invisible currents that can jar the airplane from its desired glidepath at any moment, but the firm and persistent crosswinds of the plains are not with me today.

One metric does record my steady progress and the subtle evolution of the lands below. I am now climbing a great staircase extending from the Gulf to the mountains of New Mexico. By the day’s end I will be only two thirds of a mile above Austin’s 640-foot mark, but the change is noted in my persistent cycle of climbs and descents. After each leap aloft, 76X churns out a slow climb to a comfortable cruising altitude. Tens of minutes later, I set my altimeter for the descent and find, to my dismay, that the easy glide of the let-down will be cut short by several hundred feet. Although I gained an equivalent amount of energy as I crossed the plains last week, it is harder for me to overlook the inequity of the situation now that I seem to be stuck in a constant climb.

The surficial geology of central Texas is dominated by mudstone and limestone laid down in seas during the waning age of the dinosaurs. These are a part of a package of rocks that extends in the subsurface throughout a large part of central and west Texas. There it hosts a massive store of underground water in dissolved fractures and fissures akin to those in the karst terrains of Florida. I stop periodically to sample these waters where they are extracted and used.

As I pass through the central Texas hill country, the only hints of the slowly emerging relief below are the swirling interference patterns created by the interaction of the smoothly undulating hills and the alternating layers of the rock from which they are built. These features continue to dominate the land as I travel, until, one hundred miles or so west Fredericksburg, they are suddenly overprinted with a harsher and more angular pattern. The patches of bare land below show the vigor of the recent US energy boom, in which intensive drilling and active manipulation of subsurface reservoirs has allowed engineers to wring an unprecidented fraction of the petroleum resources from the strata below. This is the stuff that powers my machine through the air, producing the lift that keeps me aloft. It comes with many costs, though, the scabs on the land surface here being just one.

Each area I’ve traversed on this trip has its own distinctive assemblage of air traffic - the training flights of Florida, the crop dusters of the plains, and the business jets that lurk at many of the city terminals waiting to whisk away their usually-unseen clients. Here, in the center of Texas, the Beechcraft King Air is king. This sturdy twin turboprop is not known for its speed or luxury, but is comfortable, versatile, and can bring a vacationing family or group of oil executives into the four to five thousand foot strips that are common across this vast ranch land. At Ozona, and then again at Junction and Fort Stockton, I land or depart in sequence with a King Air, and find others waiting ready at the ramp.

I stop at the small field in Pecos, which has an old FBO building that reminds me of a vintage fire station. Parked outside on the ramp are a trio of Cobra attack helicopters, each bearing a worn stencil reading “MARINES” on its side. Inside I find the crew, tucking into burritos that Robert, the office manager, has provided. He offers me one, which I politely and regretfully refuse. I’m still full from lunch at the diner in Fredericksburg. I ask the Marines where they are headed...it turns out we’ll meet again in El Paso later in the day.

Around the town of Van Horn the rolling hills finally give way to real mountains. These are dry, craggy ranges that seem to crumble under the relentless sunshine. My last leg of the day sees me climbing through a low pass west of the town as the sun settles toward the horizon ahead. After spending most of the past week over flat lands, it is startling to recognize that I can no longer fly direct from A to B and must pick my route around topography. I slip through the pass and climb to 10,500 feet, where the air is still and cool, and thirty minutes later let down into the quiet of a warm El Paso evening.

March 18, 2019

-Coast to coast!-

The route west from El Paso is blocked by a ridgeline of 8,000 foot peaks that, like a weir in flowing water, forces the arriving and departing air traffic through one of two gaps. The first is a slot in the ridge some ten miles north of the city, the second a tapering of the range as it descends toward the Rio Grande and the Mexican border. This morning I choose the second route, which takes me directly over downtown El Paso and within two miles of our southern border. The river itself is withered and weak, a disappointing physical marker of the much-discussed and debated boundary. Instead it is the color and texture of the two cities which sets them apart and makes them readily distinguishable. Where El Paso is grey and tan and square, hatched by the chunky structure of buildings and blocks, Juarez has the chaotic dazzle of glitter and is sprinkled by reds and yellows. From above, the contrast is remarkable.

As I slip through the gap the Rio Grande takes a northward turn, leaving the border behind and diverting into New Mexico. The cities thin and give way to desert, and here I get a glimpse of the wall, barricade, or steel slat structure...its composition is obscured by distance and height but its form is obvious as it draws a crisp, straight line across the otherwise soft landscape. Now this is what a homebound geographer must imagine a border to be, as if a giant with a pen and straight edge traced the image from the atlas with perfect precision. A thin streak, from my perspective it seems absurd that this feature could stop anything from moving across the vast expanse of desert below, but the intent of separation is clear.

I stop at Dona Anna, Silver City, and Safford. Across this stretch of southern New Mexico and Arizona the dry slopes are covered with the subtle mustard and rust colored hues of the spring desert bloom. The numerous, low ranges and peaks of this region are frequently scarred with the giant craters of open-pit mines. Penetrating hundreds of feet below the land surface these holes appear to be bone dry to their bottoms. My planning has revealed that there is subsurface water throughout the region, but in this parched environment it’s hard to imagine where it lies or where it came from.

The morning air is smooth and my confidence is high after a series of silky smooth landings. As I cross over Pinal Peak and drop into the Phoenix Basin, however, all this starts to change. Once again the land has receded, and in the midst of the drab desert is a valley of green. I drop below the ridgeline and find the air thick and warm, heated by sun-soaked vegetated surfaces. At Coolidge airport I find an Air Force recruiting exhibition, with Super Cubs towing gliders aloft for demonstration flights. These delicate, thin-winged contraptions leverage the thermal currents to climb aloft, and no doubt their pilots are much more pleased by these drafts than I am as I bounce and jostle toward the earth. As I cross the runway threshold, a current lofts 76X upward, reversing our descent in slow motion. We momentarily hang in the air, and then abruptly the air seems to be gone from under our wings. We plummet downward. I yank at the yoke to arrest our descent, though its effect seems only to minutely lessen the jarring thunk of our impact with the pavement.

From the Phoenix area I wing westward across the Mojave, with its blacked volcanic cones, and the LA basin. Phoenix and Los Angeles are both sprawling communities set in the water-starved desert. In order to sustain their ever-growing populations, the local water companies have shown great skill in securing and diverting waters from sources near and far. For our current effort, to sample groundwaters of known origin, this complex infrastructure creates a hopeless scenario. I am able to find some smaller communities in the Phoenix area that still manage their own single-source water supplies, but I toss in the cards when it comes to LA. The ninety-minute overflight of the basin, from Palm Springs to Lompoc on the Pacific Coast, is the longest uninterrupted flight of the trip so far.

And speaking of the Pacific, there it is, shimmering in the lowering sun. In terms of distance traveled, I had easily logged enough to have traversed the country days ago. But as I catch my first glimpses of the Pacific, first over the LA smog and then more vividly beyond Santa Barbara and Lompoc, I can claim without exaggeration that my first coast-to-coast flight is complete. I pause for a moment to take in the glimmer and the smell of the ocean, then taxi to runway 25 and climb into the sun, banking northwards toward Paso Robles and the end of a long day.

March 19, 2019

-The route home-

I lift off from Paso Robles Municipal Airport at a few minutes past nine and make a shallow turn to the north. The vineyards slowly recede below, and as I climb over the velvet-lined ridges of the Coastal Ranges I pick up a pleasant 25-knot tail wind. This breeze will push me all the way to Merced, but is a portent of struggles I will encounter later in the day.

I settle into smooth air at 7,500 feet and patiently twist the red mixture knob protruding from the instrument panel. This action, which has become second nature over the past eight days, slowly reduces the flow of fuel into the engine to restore harmony with the rarified air that, momentarily, will unite with the 100-octane vapor in an imperceptibly rapid burn, powering 76X’s propeller through one more revolution. Setting this balance is, in the reliable but notoriously inelegant 1950’s-era engine that powers my Cessna, akin to scanning frequencies with the dial of an old transistor radio receiver. You search a bit in one direction, then in the other, to try to find passable signal. A few minutes later, you become dissatisfied with the reception, and fiddle with the setting to little end.

The east flanks of the range fall away below me, and I catch a glimpse of red in the hills. At moments in many flights I will look out and be struck by a vague feeling of familiarity. The shape of a hillslope, the arc of a road, or the outline of a lake might trigger a memory. Every now and then, further study reveals that this is a place I’ve visited before and at ground level. Now I refer to my GPS position and cross-check charts loaded on the iPad affixed to 76X's yoke. Although it’s not marked anywhere on the map, I am able to triangulate my view as the location of the New Idria mercury mine. Eighteen years ago this spring I was wandering these hills doing my best to help UC Santa Cruz students learn the art of geological mapping. The streaks of rock we traced across the hills with great effort are laid out clear from my current vantage point, though to map them from up here would be a different and less enriching experience.

I emerge into California’s great Central Valley. Here the land is a chessboard of farm fields, cut occasionally by a long, arcing canal. The massive agricultural production of the region has been fueled, in part, by large-scale extraction of groundwater. As the volume of these fluids within the shallow crust has been reduced, the land itself has collapsed slowly and progressively, subsiding tens of feet and making the entire Valley something like a giant Floridian sinkhole.

My goal here is to sample several cities towns that, despite the notorious history of overuse, continue to use water pumped from below. This has taken some preparation, however, given that California’s other massive water projects, the canals, also crisscross the Valley. These aqueducts carry more rapidly replenished water from the massive reservoirs of the Sierra Nevada southward, toward thirsty Los Angeles. Along the way water is sipped and siphoned to provide allocations to many Central Valley communities. I navigate clear of these mountain-water towns and make stops near Modesto, Madera, and Visalia, where I know I’m getting the local brew.

Modesto marks the northernmost point of my circuitous path through California, and I turn south-southeast to parallel the giant mass of the Sierra, which lurks outside of the pilot’s side window. A reasonable pilot, reviewing the chaotic wandering of my route across the country, would wonder what madness drove this poor airman to follow such an inefficient and irrational line. Perhaps they would assume that the route was cluttered with hazards, an army of thunderheads guarding against advance and forcing a tentative hunt and retreat as gaps teased and collapsed in my path. I doubt that in a thousand guesses they would deduce my true cause. I have been making my way across the country not like the goose, on his great high-flying migration, but like the robin who scans and pecks through the litter for choice worms, occasionally making progress in so doing.

With my southward turn the winds that pushed me from Paso Robles now confront me head-on. My progress is slowed, but the change remains only a minor inconvenience until I begin to near the southern end of the great Valley. Here the land pinches up sharply between the south tip of the Sierra and the Transverse Ranges bounding the Los Angeles Basin, creating a ring of peaks rising to above 8,000 feet. I am cruising at 9,500, more than enough to slip through the many passes ahead, were they the only thing in my way. But today the winds and the land have conspired to make the passage more difficult.

As the firm southern winds encounter the arc of high terrain ahead they are forced upwards, compressing and accelerating their flow according to the same principle that speeds the flow of air over the wing surface, producing the precious lift that keeps me aloft. Unlike the smooth surface of the wing, however, the mountains were not engineered to promote orderly, laminar airflow. The winds spill over the range’s peaks and irregularities, their flow separating into giant billows and chaotic vortices. The overall pattern is one of a wave of air, rising and falling in rhythm as it sweeps across the range and into the Valley, but within each oscillation is embedded a tangle of smaller, swirling currents that can bat around a small airplane like a cat does a ball of string. Aviators call this the mountain wave.

I am now struggling with the controls and trying to maintain my 9,500 feet in an orderly and respectable fashion. As the rising and falling limbs of the wave catch me, however, this requires first forcing the nose of the airplane downward into a bone-rattling, accelerating dive, then abruptly pulling the now-emasculated ship into a near-stall struggle against an onrushing downdraft. The smarter course would be to give up my pride and allow the mountain wave to have its way with us, riding the currents up and down but trusting in their approximate balance to keep us above the slowly approaching terrain. I alert the air traffic controller that I will be maintaining a “block altitude”, signaling that approaching traffic should give me wide berth on account of my erratic flight path. I pull back on the black throttle knob to slow my ship and allow it to better absorb the increasingly severe jostling that accompanies our approach to the range. We gradually ease up and over the ridgelines, and the air begins to relinquish some of its fury. With this, a small part of the tension that has slowly accumulated in the cabin is released.

Ready for a break, I begin to let down into the Apple Valley airport, descending over the aircraft boneyard at Victorville. Apple Valley is nestled between low peaks in a high valley in the shadow of the San Gabriel Mountains, which line the northern flank of the LA Basin. Squeezed southward around the tip of the Sierra Nevada and the sprawling military airspace surrounding the three-mile-long runway at Edwards Air Force Base, my path has taken me back within tens of miles of yesterday’s westward track. The stop at Apple Valley marks my progress, however, as from here my route will turn northeast toward my final destination, Salt Lake City.

Refueled and somewhat refreshed, I set out toward home. I stop at the airport at Jean, Nevada. This well-developed strip, with two gleaming runways, appears to be built as an extension of the hulking casino which fills the space between the runways and Interstate 15. Two biplanes are practicing aerobatics three miles west of the field, and after collecting my sample I pause to watch their show. Later, I wait at the end of the taxiway as they glide in to make their graceful 3-point touchdowns and refuel.

I squeeze through the busy Las Vegas airspace and the controllers route me east of the city, over Lake Mead. I catch glimpses of the massive Hoover Dam, an icon of man’s efforts to tame the waterways of the west. Just as we were engineering solutions to conquer the skies and their fluid currents, these concrete monstrosities were being designed and erected to regulate the flows of terrestrial waters. Both Hoover and my Cessna grew out of this era, in which innovations in materials and design were leveraged to achieve control and dominance over natural forces. To large degree the control we achieved was, we now know, illusory. Although the desire lingers, and still emerges occasionally in policy and discourse, I am comforted to see the conversation of our era shifting increasingly toward achieving balance with, rather than mastery over, these forces.

Beyond Las Vegas the landscape becomes familiar. Red rock marks the transition to my home state. I am now within the reach of an afternoon leisure flight from Salt Lake, and begin to spot landmarks that have constituted the destination for my more modest adventures in the past. I pass the southernmost peaks of the long, linear Wasatch range, which I will track along the rest of my route. The beautiful dunes near Delta slip below me as I climb from that airport, my final sampling stop of the trip. As I drop into the Salt Lake Valley the sun is sinking low in the sky. Even through a windshield that marked by abundant evidence of the dense insect populations of the Central Valley, the golden gleam of the Wasatch is a stunning welcome, the most beautiful sight of my journey.

I unload my duffle and backpack one final time in front of my hangar at the Salt Lake International Airport. For the first time in eleven days I unplug my olive-green aviator’s headset from 76X’s panel and carefully wrap the cords for storage. I record engine times from the panel’s gauges and inventory my accomplishment. I made it, coast to coast, and many points in between. I have logged landings at 81 different airports and gathered 82 samples from 19 states. In 61 hours aloft I have traveled a route that totals more than 8,700 miles along roadways. Although I never lingered for long at any one site, I feel as if I have learned a bit about each place I visited or overflew. From chance encounters on the ground to little observations from above, the past week and a half has left me with context and insight that will be memorable and also of value in the work that lies ahead.

I gather up the 82 bottles that constitute the tangible product of this adventure. They all fit in a box that could not hold a volume of maps describing the ground I’ve covered. Yet we will take them to the lab, and the information they reveal will help us draw maps depicting new dimensions of these landscapes. With luck they will produce new insight, ideas, and impacts that far exceed their weight and volume. After all, we learned to fly, to tame the rivers, and to pull water from the ground where none appears to exist. We’re beginning to learn to deal with the impact of these activities. With a little ingenuity, some dedication and hard work, what’s to stop us from figuring this out?